Now that it’s full on summer, let’s check in about a topic that is pertinent for all the endurance athletes, and particularly runners, with wonky guts and/or rigid beliefs about fueling during longer efforts.

I’ve heard so many variations on the following over my years as a runner:

“I can’t eat anything before a run, ever.”

“I can’t eat anything during a run.”

“ I can’t drink anything more than a little water during a run.”

“I have no appetite for hours (or days) after a run and my GI is messed up for several days.”

“I’m not recovering from long runs or races as well as I used to.”

If you currently relate to any of those statements, I want you to know that the digestive system is highly adaptable. Gastric emptying as well as stomach comfort can be ‘trained’ during endurance activities.

Stored glycogen, or the amount of carbohydrates in our system already, are depleted after about 80 minutes at marathon pace, so for most athletes training for longer efforts, fueling with some sort of carbohydrate during exercise is essential. This training of the gut can improve the delivery of nutrients during exercise so during these long efforts, your system gets the fuel you need and are ingesting, and alleviates some (and perhaps all) of your negative GI symptoms.

How Can I Train my Gut?

What we currently know is that the stomach can adapt to ingesting large volumes of both solids, fluids, or combinations of the two.

Just think about those competitive eaters who can down dozens of hot dogs in a matter of minutes. Disgusting thought, I know, but they have to train their systems to do it! For endurance athletes needing fuel for the long run, we need to do our own version of gut training.

This happens both during and outside of exercise because eating a higher carbohydrate diet leads to our intestinal cells, called enterocytes, being able to absorb and utilize carbohydrates as fuel more efficiently.

To get sugar (carbohydrates) from our small intestine where absorption occurs into our blood, the sugar molecules mostly have to be transported across the membrane by glucose or fructose transporters. Think of a taxi transporting you from the airport to your destination. When we eat a diet high in carbohydrates, our body naturally increases the number of sugar taxis (glucose and fructose transporters).

You’ll notice some of these taxis are sodium-dependent, which is a super essential nutrient for endurance exercise, particularly in the summer, but a topic for another day.

We also know that increasing dietary intake of carbohydrates increases the rate of gastric emptying. This occurs rapidly with a change in diet, within just a few days. So what this means is that you can fuel with more carbohydrate before exercise, fuel with more carbohydrate during exercise, not feel like you’re running around with a giant, full, sloshy gut, and perform the training run or race better, because you were using the fuel you needed to perform adequately.

And, we also now have evidence that when you fuel with the appropriate amount of carbohydrates before, during and after an exercise bout, recovery from hard efforts is substantially improved.

When your body has all the sugar taxis it needs to get carbohydrates out of the digestive system and into the blood stream for circulation and use as fuel as quickly and efficiently as possible, and our body gets used to using carbohydrates added on the go as fuel, the chances of developing GI complaints during exercise are much smaller.

Win, win, and win, in my opinion.

How Much Carbohydrate Can and Should I Be able to Tolerate ?

How much carbohydrates you need or should consume during exercise depends on a few factors. One, how long you’re going to be out there. Two, the intensity of the effort. And three, your gender.

Exogenous carbohydrate oxidation, or the amount of carbohydrates we can use during exercise, peaks around 60 grams per hour when it comes from glucose only. When fructose is ingested in addition to glucose, carbohydrate oxidation rates are elevated above 60 grams per hour, to 90 to 120 grams per hour (when the gut has been trained). In women, however, we have evidence that carbohydrate oxidation rates appear to be maximized at about 60 grams of carbohydrates per hour (2). If you’re a female and looking to maximize your fueling and racing/recovering capacity, you can experiment with ingesting more than 60 grams per hour. This upper limit will likely be individual.

The current guidelines for fueling are to take in up to about 60 grams per hour of carbohydrates for exercise lasting up to two hours.

And when the effort lasts longer than 2 hours, men should experiment with increasing their intake to slightly greater amounts of carbohydrate (90g/hr), but women may feel best at sticking with 60 grams per hour. These carbohydrates should be a mix of glucose and fructose or maltodextrin and fructose. Virtually every sports nutrition product for use during exercise includes a mixture of carbohydrates these days so most people will not need to worry about getting the different sources. And most do-it-yourself whole food fuel sources will also include both fructose and glucose.

Note that sucrose, which is contained within many whole foods and is also what makes up simple table sugar, is a disaccharide, meaning it has two different sugar compounds, fructose and glucose.

Here’s another way to look at the timeline of fueling needs:

| Exercise Duration | 0-59 minutes | 1 hour | 2 hours | 2.5 hours | 3 hours |

| Grams of Carbohydrate Per Hour | none | 30 | 30-60g : women Up to 70 g/hr: men (higher intensity = higher need) | 30-60g : women Up to 70 g/hr: men | 60 g: women (can experiment with more) Up to 90 g: men (can experiment with up to 120 g) |

How Long Does Training the Gut Take?

If you’re training for a race and practicing fueling during long efforts, it doesn’t take more than a few days to a couple weeks to increase those sugar taxis in your gut. Based on animal data, an increase in dietary carbohydrate from 40 to 70% could result in a doubling of SGLT1 transporters over a period of two weeks (1).

But it’s important to practice your race nutritional strategy in training, get used to higher volumes of solid or liquid intakes, and higher carbohydrate intakes both during and outside of training.

As always with fueling for sports, it will take a little individual experimenting and tweaking to find what works for you so you’re less likely to end up looking like this during your next long run or race:

Will Training My Gut Fix all my Exercise-Related Digestive Woes?

Perhaps following the above recommendations will be a simple answer to fixing all your exercise-caused angry/sad midsection woes.

But many people with digestive systems that are more prone to upset also need to pay special attention to what you are and aren’t consuming, and how much you’re eating in all the hours outside of training. This can be very individual.

Want to Know More?

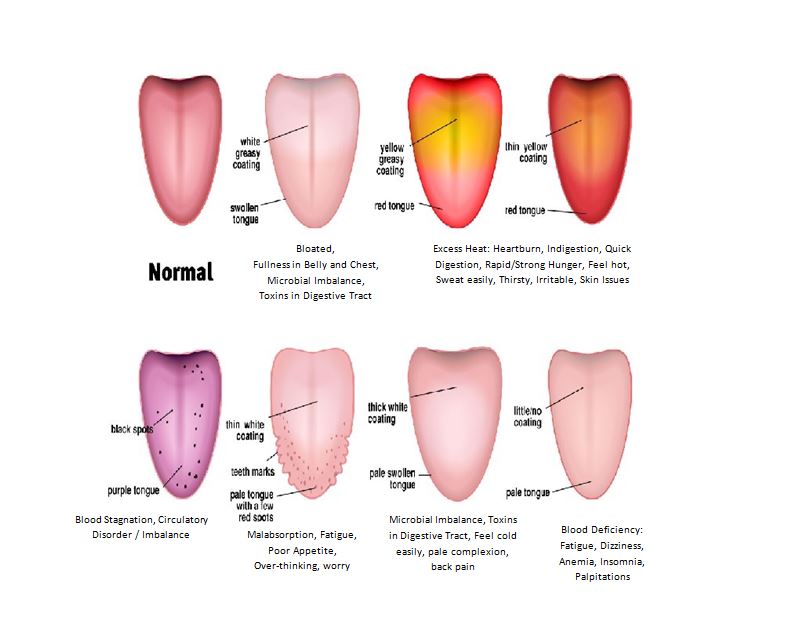

Within my nutrition practice, I specialize in digestive imbalances. Often when we’re experiencing chronic GI distress, fatigue, and/or malabsorption of foods and nutrients, there will be imbalances in several systems of the body simultaneously. I shared more about this topic in the nervous system’s role in part 1, the immune response and subsequent inflammation in part two, gut microbes and dysbiosis in part three and the importance of chewing our food in part four. Check those out or reach out to me for more personalized support for gut healing, or to go from not being able to tolerate fueling, to training your gut for the amount you need.

References:

1). Jeukendrup, A.E. (2017). Training the Gut for Athletes. Sports Medicine, 47(Suppl 1): S101-S110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0690-6

2). Wallis, G.A, et al. (2007). Dose-response effects of ingested carbohydrate on exercise metabolism in women. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 39(1): 131-8. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000241645.28467.d3.